Ladies' Guidelines

Restrained Elegance: Ladies' Attire in Antebellum Buckingham County, Virginia

Sarah Alexander Seddon Bruce, wife of Charlotte County planter, Charles Bruce. Miniature watercolor by George Lethbridge Saunders, ca. 1850. Belonging to one of the wealthiest families in Southside Virginia, Mrs. Bruce epitomizes the ideal of "restrained elegance," the hallmark of a Virginia belle.

As seen from our study of men’s clothing in antebellum Virginia, rural Virginians’ attitudes towards fashion differed greatly from those of their urban counterparts. In The Sweetness of Life: Southern Planters at Home, Eugene Genovese cites scores of primary sources documenting the ways in which inhabitants of cities and towns across the South competitively pursued the latest European fashions, expending great time, wealth, and energy to achieve and maintain a flawless appearance, and availing themselves of every opportunity to flaunt their finery.(1) In an 1853 article from the New York Daily Times entitled “The South,” Frederick Law Olmsted remarked on Richmonders’ obsession with "high dress" which, he claimed, exceeded that even of New Yorkers:

Everybody in Richmond seemed to be always in high dress. You would meet ladies early on a drizzly day, creeping along their muddy streets in light silk dresses and satin hats; and never a gentleman seemed to relieve himself of the close-fitting, shiny, black, full evening suit, and indulge in the luxury of a loose morning coat.(2)

In A Journey Through the Seaboard Slave States, Olmsted commented on displays of high fashion in Richmond's African American community.

Many of the colored ladies were dressed not only expensively, but with good taste and effect, after the latest Parisian mode. Many of them were quite attractive in appearance, and some would have produced a decided sensation in any European drawing-room. Their walk and carriage was more often stylish and graceful than that of the white ladies who were out.(3)

By contrast, rural Virginians of all classes had a reputation for their conservative attitudes towards dress and personal adornment, and, as we shall see, a New Yorker’s high estimation of the sort of “expensive” apparel and “stylish” bearing fit to produce a “sensation” — terms which nowhere appear positively in rural Southerners’ vocabulary during the antebellum period — would have held little sway in the countryside.

American dress, 1848. Note similarity to dress worn in the image to the right.

Charlotte & Lucy Taylor, daughters of William and Elizabeth Taylor, Richmond, Virginia. ca. 1845-50.

Virginia girls, ca. 1845-50, exemplifying the plain style of dress common among rural Virginians.

"The Amber Necklace" by German-American artist, Emanuel Gottlieb Leutze, 1847

The people of Buckingham County, like most of Virginia and Southside especially, were religiously and politically conservative, and clothing was one of the most direct personal expressions of their worldview. Whereas country gentlemen in the Old Dominion, often in conscious defiance of city ways and their influence, chose a plain, rustic wardrobe which communicated Christian modesty and republican virtue, terms they often employed, period sources indicate that country ladies, motivated by the very same cultural values, cultivated an eye for beauty and strove to present and maintain a graceful, composed, and tasteful aesthetic in their personal appearance that was at once modest and attractive.

This concern for beauty is not to be confused with the vanity associated with cities in antebellum times. Elizabeth Fox-Genovese articulates this critical distinction in her study Within the Household: Black and White Women of the Old South:

A lady distinguishes herself by her observation of fashion’s conventions; lavish display for its own sake provided no substitute…. Fashion articulated class position; extravagance defied it. A lady had to know the difference, had to manifest in her person a restrained elegance that simultaneously betokened internal self-control and solid male protection.(4)

But what defined extravagance? Where was the line between “restrained elegance” and “lavish display?” Let us consider the answers given by some of antebellum Virginia’s most influential voices, its preachers.

In reference to women’s increasingly low necklines, short sleeves, and exposed shoulders, John Early (1786-1873), a firebrand Methodist circuit rider from Bedford County, Virginia who regularly ministered in Buckingham, denounced the sinful display of “naked breasts and elbows,” and, on at least one occasion, which Early proudly recorded in his diary, he did not hesitate to confront a woman directly about her extravagant jewelry.(5, 6) Early was not alone in his thinking. State Senator A.C. McIntosh of Alexander County in North Carolina’s western Piedmont could have been speaking for rural Virginians when he wrote home to his wife of a Christmas party he attended in Raleigh in 1848, “I confess there was a little more of the breast and arms naked than would look becoming in the country.”(7)

Robert Lewis Dabney, the renowned Southern Presbyterian theologian who taught at Union Theological Seminary near Farmville, Virginia and later served as Stonewall Jackson’s chief of staff, was outspoken in his disapproval of extravagant fashion among men and women alike. This was the case with Dabney even as a student at the University of Virginia. In 1840, the twenty year old budding theologian wrote home to his mother in rural Louisa County, Virginia,

You will not be any less surprised when I tell you that I saw a very venerable lady, the wife of one of the professors, who has all the honors of age upon his head, and who is herself not so young as she formerly was, having had three husbands besides the present, walking out this cold, windy day in light salmon slippers, with stockings to correspond. How would it look to see old Aunt Polly hop out of her carriage at Providence [the country church attended by the Dabneys], in salmon slippers, pink merino, crimson velvet bonnet and blonde veil? I have no doubt the old lady, with her refined taste in dress, would almost faint at the idea. Yet her appearance would be identically that of the old lady I speak of.(8)

Dabney’s characterization of his Aunt Polly as a lady at once humble, yet possessed of a “refined taste in dress” betokens the popular idea that “a lady distinguishes herself by her observation of fashion’s conventions” while “lavish display for its own sake” communicates only vanity.

Lucy Goode Tucker Chambers, Mecklenburg County, Virginia, ca. 1845-50. Mrs. Chambers' attire typifies the conservative aesthetic of antebellum Virginia. Dabney's Aunt Polly likely dressed after the same fashion.

Margaret "Peggy" Mackall Smith Taylor, wife of President Zachary Taylor ca. 1845-50

Unidentified woman, Charlottesville, Virginia, 1845

Julia Gardiner Tyler, wife of President John Tyler, ca. 1845-50

How then did ladies in rural Virginia dress? One of our best accounts of everyday ladies’ attire in the Virginia countryside comes from a letter Dabney wrote to his wife reporting on his journey from their home in Prince Edward County to his mother’s house in Louisa. Along the way, Dabney stops by the farm of his friend Mr. Harrison in Cumberland County where he finds, “all the ladies of the family in calico, except Mrs. ——, who, being poor, was finer. She had on a black stuff dress in the evening, and white cambric wrapper in the morning.” “Now this is the way,” Dabney declared of the Harrison ladies, “rational people live, who really are rich.”(9) In the same letter, Dabney describes his sister-in-law Louisa,

She is a charming woman, and none the worse in my eyes for being a "fruitful vine." I came right in on her without two seconds' warning…. Louisa's dress, I suppose, cost (including everything but breastpin) about $4, a very plain lawn, a neat little collar, and a band of black ribbon, with a bow around her fair hair, but all was clean, tidy and fresh. She did not have to run and hide, as certain other females would be very apt to have to do, and undergo a hurried primping, to make herself presentable to a brother-in-law from a distance; but, hearing my step on the door-sill, looked up, and rising, came at once to meet me as she was.(10)

Simple yet thoughtfully composed, the same mild and graceful aesthetic ideal is exhibited in formal portraiture of the period which customarily depicts Virginia ladies in modest black dresses with neat lace-edged collars adorned with a brooch or breast-pin as well as in less formal settings such as those presented by Dabney.

Describing the simple, yet refined and graceful appearance of ladies at a Virginia barbecue in 1850, one observer wrote, “White dresses and scarlet shawls are as numerous as the summer flowers upon the neighboring hills.”(11) Such accounts demonstrate that modesty and elegance were in no way inconsistent with one another, but in fact went hand in hand accourding to the aesthetic ideal for ladies in rural antebellum Virginia.

Lynchburg Virginian, June 17, 1850

Lynchburg Republican, November 15, 1847

Quilt from "Little England" Plantation, Gloucester County, Virginia, c. 1840, exemplifying print styles popular in Virginia.

Lynchburg Republican, March 22, 1847

Lynchburg Republican, May 18, 1846

While modesty in one’s attire was upheld as a virtue among ladies in this social and cultural context, it would nonetheless be wrong to say that their manner of dress was always plain or stereotypically puritanical, especially among younger ladies. Numerous photographs, paintings, primary accounts, and inventories of the sorts of fabric being sold in Lynchburg and Richmond indicate the wide variety of colorful, interesting, and attractive styles which would have been available to middle and upper class women in Buckingham County, all without compromising their conservative values. Scottish-American artist William Thompson Russell Smith’s 1836 painting of a river baptism in Virginia shows dresses and parasols in a cheerful array of pastel colors, and primary sources reveal that a similar palette was freely enjoyed by girls at the Buckingham Female Collegiate Institute in the 1840s.

"Baptism in Virginia" by William Thompson Russell Smith, 1836

Established in 1837 under the patronage of the Methodist Church, the Buckingham Female Collegiate Institute was the first chartered college for women in Virginia and drew an exclusive set of students from Virginia and across the South, including a noteworthy contingent of young ladies from Buckingham and neighboring counties. Although the Institute struggled financially throughout its years of operation, it was the county’s most prestigious landmark until the stresses of war finally forced it to close its doors for the last time in 1863.

Rev. Henry James Brown's painting of Buckingham Female Collegiate Institute used as cover art for "Buckingham Polka" sheet music, published 1852.

An illustration of the school made around 1850 by one of its instructors, Rev. Henry James Brown, painter, preacher, and planter from neighboring Cumberland County, features figures strolling the grounds in colorful dresses and bonnets, an image confirmed by the words of the students themselves. We are fortunate to have access to extensive records from one of these students, Mary Catherine Molloy, later Gannaway, a native of Buckingham who attended the Institute from 1837 to 1840 when she graduated at the age of sixteen. In 1840 Mary Catherine wrote home to her mother,

Mrs. Nesbitt has finished my dress by the latest French style. It has fifty yards of pale green ribbon on the skirt, turned and twisted and looped in design, but which makes me think of our parlor at Christmas when running cedar is hung everywhere. The waist is, I think, very pretty, of a paler color, and flattering to me. When I tried it on yesterday Mrs. Nesbitt cried, “Child, you look almost as handsome as your mother, and ’tis I that did it!” Did you ever hear the like?(12)

Mary Catherine Molloy Gannaway, ca. 1850-55. Student at Buckingham Institute 1837-40.

A later photograph of Mary Catherine from the 1850s demonstrates her appreciation for fine materials and conservative, yet fashionable design. In another account, Bessie Applewhite of Suffolk, Virginia shared her mother’s recollections of her time as a student at the Institute during the 1850s:

In those days, the graduates did not wear caps and gowns, nor did they confine themselves to the later traditional “white organdie,” but wore whatever sort of gown they or their parents preferred. My mother’s dress was of “peach-blow brocaded silk.(13)

With their allusions to pale green and peachblow dresses, these accounts reaffirm the popularity of pastel colors for ladies’ apparel in antebellum Virginia. It is worth noting, however, that these are dresses made for special occasions.

Parisian fashion plate, 1845. Note pale green and peach colors both mentioned in descriptions of dresses worn by students at Buckingham Institute.

Yet, even when Virginia belles dressed up, they were never noted for extravagance or vanity. Robert Lewis Dabney recorded one New Yorker’s surprised response to the scene at an evening gathering of the Virginia State Agricultural Society in the 1850s:

I thought that I was going to be amused with the ways of rustics; but when I saw inside of those parlors, I had sense enough left to see that I was face to face with the most elegant, cultured, and graceful assemblage that I had yet seen anywhere. Why, those evening costumes — what a union they were of refined taste and grace, with appropriateness and moderation! I never saw so many accomplished women in one set of parlors, so marked by gentle dignity, affability and culture.(14)

Afternoon dress, American, 1843

Printed cotton day dress, c. 1850

Muslin day dress, ca. 1840-45

Portrait by portrait Virginia artist Charles Burton, ca. 1840

Miniature by Edward Samuel Dodge, ca. 1850, portrait artist working in Virginia, South Carolina and Georgia

When asked by his host where he supposed these ladies acquired their “graceful costumes,” the New Yorker replied “From Paris, or New York, of course.” “There you are wrong again,” replied the Virginian,

I know the habits of those families thoroughly. On nine-tenths of those costumes no paid modiste ever put a finger; they were fashioned by the young ladies at home, with the assistance, in some cases of elder sisters and aunts. Did you not perceive, sir, that the most of their materials were inexpensive? Was there any parade of diamonds? No; on the contrary, little jewelry of any sort. Those charming combinations of graceful forms and subdued colors in those dresses were simply the expression of the sober and refined home taste.(15)

While silk evening gowns would not be seen at a country barbecue or camp meeting, these remarks testify to the standards of modesty which prevailed among country ladies even on the most formal occasions as well as to the frugality and self-reliance practiced by rural Virginians of all classes, including those with means to afford the finest materials and employ the most prestigious, big city tailors.

Of necessity, women of lower social rank and lesser means shared in these practices. Regarding the clothing of female slaves in Virginia, Frederick Law Olmsted observed,

The women have two dresses of striped cotton, three shifts, two pairs of shoes, etc. The women lying-in are kept at knitting short sacks, from cotton which, in Southern Virginia, is usually raised, for this purpose, on the farm, and these are also given to the negroes. They also purchase clothing for themselves, and, I notice especially, are well supplied with handkerchiefs which the men frequently, and the women nearly always, wear on their heads. On Sundays and holidays they usually look very smart, but when at work, very ragged and slovenly.(16)

Washerwomen, Yorktown, Virginia, 1862

Homespun cotton fabrics from the plantation of Mrs. J. J. McIver, Darlington, South Carolina, ca. 1860. Collection of the Museum of the Confederacy.

Homespun osnaburg from the plantation of Mr. Mitchell King, South Carolina, ca. 1860. Cotton, hand-spun and woven. Collection of the Museum of the Confederacy

Other sources corroborate Olmsted’s account. In “What I Did with my Fifty Millions,” Buckingham County author George William Bagby describes the typical slave women of Southside Virginia “in striped homespun,” and we find numerous references to the same in runaway ads for female slaves in Richmond and Lynchburg newspapers.(17) In addition to surviving examples of striped fabric woven on plantations, we also have photographic documentation, one of which depicts black washerwomen in Yorktown, Virginia in 1862, confirming the use of striped fabric for slaves’ dresses.

"The Cook" from Virginia Illustrated, by David Hunter Strother, 1857

Unidentified woman, ca. 1850.

Handwoven samples of striped linsey reproduced from runaway ads ca. 1770-1783 by Peg Critser of Friends in Fiber, via Wm. Booth, Draper at the Sign of the Unicorn.

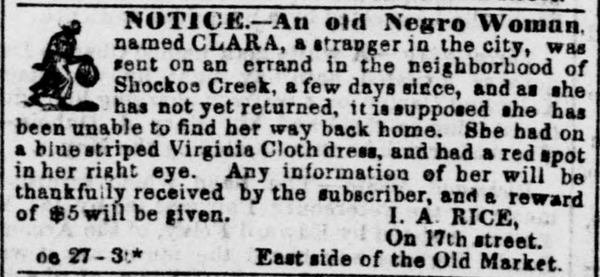

Regarding materials, the terms lindsey, homespun, cotton, and calico predominate in runaway ads. We also find references to female slaves wearing Virginia cloth, a coarse, homespun, jeans material rarely if ever represented in reproductions of ladies’ clothing. One instance appearing in Richmond's Times Dispatch on October 27, 1856 informs us of an "old Negro woman" who wore "a blue striped Virginia cloth dress.” Period images and written accounts such as Olmsted’s reveal that headwraps were ubiquitous among African American women in the Old Dominion, although bonnets, linen caps, and occasionally men’s slouch hats appear as well. Several sources, including David Hunter Strother’s Virginia Illustrated, indicate that it would not have been uncommon for female slaves to go about in old, low-quarter or cut down, men’s or boys’ shoes, often worn as slippers without laces.

Times Dispatch, October 27, 1856, Richmond, Virginia

Although less frequent, instances of female slaves wearing finer materials such as mouslin de laine and yellow lawn, to cite two local examples, also appear in runaway ads. Meanwhile, the photographic record reminds us that many slaves were better-clothed than poor whites, a circumstance confirmed by period commentators like Frederick Law Olmsted among others. One example from our region is an 1853 likeness of Mary Brice, a domestic servant at “Point of Honor” in Lynchburg. The image shows Brice wearing a print wrapper or work dress with cameo brooch while holding a folding fan adorned with a painted leaf pattern.

Unknown group, Virginia, ca. 1850. Note striped dress.

Slave woman and child, Richmond, Virginia, 1840s

Lucy Cottrell with granddaughter of George Blaetterman, German-Born professor at University of Virginia, Charlottesville, ca. 1845. Blaetterman acquired Lucy and her mother Dolly from the estate of Thomas Jefferson.

Mary Brice, servant at "Point of Honor," Lynchburg, Virginia, ca. 1853

The nicer clothing seen in this image and others may be accounted for by the common practice whereby slaves were frequently given old clothes handed down from a master or mistress. Alternatively, some slaves may have purchased clothing for themselves with money earned from side work. Or it may simply be a reflection of the fact that wealthier slaveowners also had greater means with which to clothe the men and women who worked for them, and had an interest in seeing that their house servants in particular were well-dressed.

"Aunt Charlotte Anne" Lawson, Captain Henry Tayloe's Windsor Plantation.

Probably free woman, Alexandria, Virginia, early 1860s. Representative of everyday dress of field slaves, free blacks, and poor whites. Although dating to a later era, overall appearance would have changed little. Some sources indicate that free blacks tended to be more poorly clothed than many slaves in rural areas, Period photographs of poor white women in the South are virtually nonexistent.

By far, poor white women are the single most undocumented demographic in the antebellum South. However, we may reasonably infer that their clothing, apart from culturally distinctive items like the headwrap, typically resembled that of slaves, especially in terms of the coarser, homespun materials used. Whether or not they would have worn the striped fabrics so closely identified with female slaves is harder to say. Judging from period accounts of relations between poor whites and blacks in Virginia at this time, it may have been that lower class white women avoided this pattern. According to Olmsted, "Poor white girls were never hired out to do servant work, but would come and help another white woman about her sewing or quilting, and take wages for it. But these girls were not very respectable generally, and it was not agreeable to have them in your house.”(18) Thus, it is less likely that poor white girls, unlike many female domestic slaves, would have been the beneficiaries of cast off clothing from the well-to-do. Similarly, free blacks were often more poorly clothed than slaves, especially in rural areas, although we also find instances of successful freedmen and their families in antebellum Virginia, some of whom earned wealth and respect in their communities as batteau captains.

hi

NOTES

Participants will be portraying locals gathered for an “old Virginia barbecue” on Saturday and a camp meeting on Sunday. Impressions should be representative of Buckingham County, Virginia, circa 1850. Fashions from the 1840s are strongly encouraged, but conservative looks from the 1850s are also acceptable. Impressions may range from upper middle class to poor. Barbecues and camp meetings were focal points of rural community life in antebellum Buckingham County and places like it across the Old South. These iconic events in the rural social calendar brought together all manner and class of folk from the surrounding area, from planter to poor white, slave and free. To recreate the cross-section of society one would have witnessed on these occasions, we welcome a healthy mix of impressions appropriate to our specific setting in rural Southside Virginia. Please consult the preceding article and material in the History section of this site for inspiration and guidance as you build your impression.

Upper class and middling impressions should dress for leisure in an outdoor setting during the summer. Excessively formal or extravagant attire should be avoided. Lower class impressions may dress for work or leisure according to which is more appropriate to one's duties for the weekend. Although low in the social order, slaves could be well-dressed depending on their role.

Ladies’ attire of the 1840s through early 1850s is characterized by smooth sloping shoulders, an elongated waist, and soft bell-shaping of the skirts. There are a variety of bodice styles and neck treatments to choose from. Fan fronts are most common for this period, but most we also see examples ranging from smooth and simple princess seams to revers-inspired shawl fronts. Skirts are either left smooth and without embellishment or treated with ruffles or flounces. Hoops are less appropriate for the time and place we are portraying. Instead, layers of petticoats, held out primarily with a corded petticoat, are used to produce the soft bell effect.

Corset design changed dramatically over the course of the 1850s. While corsets of the style worn from the 1840s through early 50s are preferred, later designs are acceptable. In previous years, participants have discovered that a typical 1840s style fan-front bodice conveniently hides the characteristic profile of an 1850s or 60s style corset worn underneath to provide the necessary structure for an overall period-correct appearance.

For middle and upper-class women in rural antebellum Virginia, plaid, printed or solid color cottons, rather than silk, would be most appropriate for everyday summer-wear and outdoor social events of the sort we will be portraying at Batteaux and Banjos. Sources indicate a preference for pastel colors among the well-to-do. Plaids and simple check patterns are extremely common for everyday and plain folk. Printed designs in the 1840s are characteristically larger than later styles, typically vertically oriented, and include more forms within designs to create a very “busy” appearance (stripes, zig-zags, ogees) or consist of two to three components spread out in a measured manner across the field. Sources indicate that female slaves in Virginia typically wore dresses of striped homespun. Lindsey and coarse homespun cotton were the most common materials for slaves and poor whites.

Except for young girls whose clothing often featured short sleeves and boat necks, women should generally favor sleeves which descend past the elbow and less-revealing neck treatments rather than short sleeves (above the elbow) and low necklines. A chemisette may be added to make a dress with a lower neckline more modest in appearance. Jewelry should be understated. A brooch, simple earrings, and a wedding band would be quite sufficient for a well-to-do lady of the Old Dominion; anything more would be considered vulgar. For headwear, straw or palm-leaf bonnets are highly appropriate for summer in Virginia. Bergère style straw or palm-leaf hats are found in period illustrations and advertisements from Lynchburg and Richmond. Slat and other period-correct bonnets in a variety of styles and materials are also welcome. Traditional headwraps are highly appropriate for African American women in the period. Eyewear must be historically accurate. Other accoutrements you may wish to bring include period correct baskets, carpet bags, market wallets , cloth or burlap sacks, and or other period appropriate forms of luggage. Please no canteens, haversacks, or other military paraphernalia.

For your own convenience

PLEASE BRING:

1. Cup (tin, pewter, earthenware, glass, or china)

2. Plate or bowl (tin, pewter, china, earthenware, wood, or gourd shell)

3. Period correct utensils

4. Tent and optional fly (Wall or wedge preferred. Please avoid military-style dog tents.)

5. Groundcloth (oilcloth preferred, gum blanket as last resort)

6. Lantern and candles

7. Bedding (quilts, coverlets, wool blankets, and tick mattresses all welcome)

8. Water in period correct containers (bottles, jugs, jars, or gourds, no canteens)

9. Period correct seating (simple folding camp-seats, lightweight chairs)

10. Period correct food and necessary cooking implements. (no "cold handle" skillets)

m

BIBLIOGRAPHY

1. Genovese, Eugene Dominick, and Douglas Ambrose. The Sweetness of Life: Southern Planters at Home. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018. 116-126

2. Ibid., 123

3. Olmsted, Frederick Law. A Journey in the Seaboard Slave States with Remarks on their Economy. New York: Dix & Edwards, 1856. 28

4. Genovese, Eugene Dominick, and Douglas Ambrose. The Sweetness of Life: Southern Planters at Home. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018. 117

5. Ibid., 117

6. Early, John. “Diary of John Early, Bishop of the Methodist Episcopal Church, South (Continued).” The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, Vol. 38, no. 3 (1930): 251–58.

7. Genovese, Eugene Dominick, and Douglas Ambrose. The Sweetness of Life: Southern Planters at Home. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018. 119

8. Johnson, Thomas Cary. The Life and Letters of Robert Lewis Dabney. Richmond, Virginia: The Presbyterian Committee of Publication, 1903. 61-62

9. Ibid., 188

10. Ibid., 189

11. Lanman, Charles. Haw-Ho-Noo: or, Records of a Tourist. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Grambo and Co., 1850. 95

12. Shepard, William. “Buckingham Female Collegiate Institute.” The William and Mary Quarterly 20, no. 3 (1940): 345. 358

13. Ibid., 366

14. Johnson, Thomas Cary. The Life and Letters of Robert Lewis Dabney. Richmond, Virginia: The Presbyterian Committee of Publication, 1903. 192

15. Ibid., 193

16. Olmsted, Frederick Law. A Journey in the Seaboard Slave States with Remarks on their Economy. New York: Dix & Edwards, 1856. 112

17. Bagby, George William. Selections from the Miscellaneous Writings of Dr. George W. Bagby. Richmond, Virginia: Whittet & Shepperson, 1884. 292

18. Olmsted, Frederick Law. A Journey in the Seaboard Slave States with Remarks on their Economy. New York: Dix & Edwards, 1856. 83

z