Gentlemen's Guidelines

Homespun Aristocracy: Men's Attire in Antebellum Buckingham County, Virginia

"The Institute Store" as it appeared ca. 1880. Established in 1837, it served the small, rural community around Buckingham Female Collegiate Institute in southeastern Buckingham County.(1)

While men in Southern cities like Richmond and Charleston customarily dressed to the nines and observed the latest trends in fashion, rural Virginians of all classes had a reputation for their plain, rustic style of dress which prioritized comfort and practicality over fashion and formality. Country gentlemen in Virginia even cultivated this aesthetic. In 1807, Supreme Court Justice Joseph Story of Massachusetts remarked, “Virginians have some pride in appearing in simple habiliments,” and more than one observer noted a certain “carelessness” which characterized the attire of country gentlemen and plain folk alike in the Old Dominion.(2)

Corroborating these impressions, our most detailed picture of everyday men’s attire in antebellum Buckingham County comes from the pen of one of her native sons, George William Bagby. In "My Uncle Flatback's Plantation," Bagby writes in his inimitable style,

I couldn't have gone the ancient costume. It is picturesque, does well for marble, and for historical paintings in oil, but it is sadly unfit for a citizen of Buckingham or Prince Edward. Imagine a man walking through a new ground, or a ploughed field, with a great sheet flapping at his calves. He would feel worse than a woman. Consider him in a brier patch. How could a body get over a fence, ride a horse, or chase a hare, say nothing of climbing for coons? In the saddle, my breeches have a grievous tendency upward anyway, as if the washerwoman had starched them with leaven; what on earth would become of me in a toga? No, you painters keep your grand historical wardrobes. Give me a straw hat, an oznaburg shirt, no waistcoat, tow-linen pantaloons, with yarn "gallowses," home-made cotton socks and a pair of low-quarter shoes, moderately thick-soled, made by Booker Jackson.(3)

Well-suited to the environment and traditional lifestyle of rural Southside Virginia , the wardrobe Bagby describes is homespun and practical from top to toe. Several examples of this rustic "uniform" may be seen in a rare nineteenth-century photograph from Buckingham County depicting men on the front porch of a country store.

Sketch of a boatman by George Caleb Bingham. Note: shoes worn as "slippers" without laces.

Frederick Law Olmsted of New York recorded the same preference for plain, comfortable clothing in his account of a country gentleman he encountered while traveling through Southside Virginia in the early 1850s:

Although Mr. W. was very wealthy (or, at least, would be considered so anywhere at the North), and was a gentleman of education, his style of living was very farmer-like, and thoroughly Southern. On their plantations, generally, the Virginia gentlemen seem to drop their full-dress and constrained town-habits, and to live a free, rustic, shooting-jacket life.(4)

This stands in stark contrast to the penchant for extreme formality Olmsted observed in Richmond:

Everybody in Richmond seemed to be always in high dress. You would meet ladies early on a drizzly day, creeping along their muddy streets in light silk dresses and satin hats; and never a gentleman seemed to relieve himself of the close-fitting, shiny, black, full evening suit, and indulge in the luxury of a loose morning coat.(5)

The words of John Randolph confirm Olmsted’s observations. Returning home from Congress to “Roanoke,” his plantation in Charlotte County, Virginia, Randolph writes:

When I cross the Potomac I... put on the plain homespun, or, as we say, the “Virginia cloth,” of a planter, which is clean, whole, and comfortable, even if it be homely.(6)

While high collars, close-fitting neckstocks, and lustrous suits of black broadcloth were de-riggeur when sitting for formal portraits, Virginia planters like John Randolph habitually dressed down when going about their daily business.

Randolph describes his attire as being comprised of Virginia cloth, a term widely used in the 18th and 19th centuries to denote a coarse, homespun, jeans material, typically twill, featuring a cotton warp and wool weft which, as the name implies, was traditionally woven on Virginia farms and plantations, although not exclusively produced there. Period advertisements, runaway ads, and other sources, most often refer to Virginia cloth in shades of light gray, dark gray, drab, pale brown, walnut-dyed, and black or “dark-dyed.” We also find references to blue-dyed, striped, and occasionally green-dyed Virginia cloth.

In his diary, the esteemed agricultural scientist and fire-eater from the Old Dominion, Edmund Ruffin, alludes to a “full suit of Virginia cloth” which he took great pride in wearing and laments its loss to the Yankee troops who plundered his home in 1864.(7) This same suit, which Ruffin wore during the firing on Fort Sumter and at the Battle of First Manassas, can be seen in a famous series of photographic likenesses he sat for in Charleston during the spring of 1861.

Edmund Ruffin in his suit of homespun Virginia cloth, 1861. Note the fabric's characteristic coarse, striated texture.

Robert Lewis Dabney, the renowned Southern Presbyterian theologian who taught at Union Theological Seminary near Farmville, Virginia, later served as Stonewall Jackson’s cheif of staff, and, according to his earliest biographer, Thomas Cary Johnson, was himself known to wear homespun, gives us a revealing annecdote from the 1850s involving “A Surprised New Yorker” who happened to witness a portion of the annual meeting of the Virginia State Agricultural Society. Following an extraordinarily erudite lecture, the New Yorker’s host, the pastor of a Richmond church, sought his guest’s opinion.

He answered, “Oh! of course I was charmed with the discourse; it was a model of scientific clearness, but I feel one great objection to it.”

“What is that?”

“That it was entirely above the comprehension of an audience of clodhoppers, and must have gone clean over their heads.”

The Richmond man said, “So you think that it is an audience of clodhoppers?”

“Why, yes, of course, or at least of yeomen. Is it not a farmers' society? And the general aspect of plainness, not to say rusticity, including even the leaders upon the platform, confirms me.”

“Well, did you notice that iron-gray old gentleman on Dr. McGuffey's right, with his long locks and plain gray suit?”

“Oh! yes; rather a striking-looking old codger, one of the oldest and most influential of the clodhoppers.”

"Just so,” said my friend; “that is the famous Edmund Ruffin, Esq., perhaps the foremost regenerator of Southern agriculture, the eminent man of science, author and editor, the lord of inherited acres, deriving almost a princely revenue from them, and the high gentleman and incorruptible patriot.”

“Indeed!” said the New Yorker, dryly.

“I will try you again,” said my friend. “You noticed the portly old gentleman on Dr. McGuffey's left, with the flaxen hair and placid blonde face? He was dressed in a decent suit of home-made black jeans, and had on plain walking shoes, with dust on them. Who do you suppose that was?”

"Oh! of course I noticed him; studied him, indeed, as an interesting specimen of the old rustic Hodge, retired upon his earnings.”

"Well, that was Franklin Minor, Esq., of Albemarle, an M. A. of the great State University, an elegant classicist, and principal of the most famous 'fitting school' in Virginia, and also the administrator of his splendid inherited estate of Ridgeway."(8)

"Southern planters," ca. 1850. Note fall front trousers.

Another notable Virginian, Rev. John Early (1786-1873), a circuit-riding preacher who regularly traversed Buckingham County and a leading light of the Second Great Awakening in Southside Virginia and the Carolinas, remarks on a coat of “Virginia homespun” he was given:

The Lord remember Sister Walker for her charity and labor of love. She gave me a beautiful Virginia homespun coat which was more suitable for Virginians to wear than any other cloth and especially Methodist preachers.(9)

On another occasion, Rev. Early tells of a “Virginia cloth waistcoat” he received (10). And, of Thomas Jefferson, who is known to have raised both cotton and wool for the production of homespun on his plantations, former slave Isaac Granger Jefferson (1785-1850) recalled, "Old master wore Vaginny cloth."(11)

Other types of jeans cloth were available in varying grades with Kentucky jeans and cassinette being two popular finer quality options in the 1840s and 50s. One listing published in the Lynchburg Virginian on November 7, 1836 advertises “Kentucky Jeans, a handsome article for gentlemen’s wear.” Blue-dyed Kentucky jeans was especially popular. Still, nothing displaced drab Virginia cloth as staple and fixture of men’s wardrobes across all classes in rural Virginia.

Lynchburg Republican, June 10, 1850

Lynchburg Virginian, February 12, 1846

Lynchburg Republican, March 22, 1847

Lynchburg Republican, May 18, 1846

It has often, and erroneously, been asserted in the living history community that jeans cloth was produced and used primarily for the clothing of slaves and, therefore, is inappropriate for middle and upper class impressions. While this may be true in some historical settings, the accounts presented above and many more like them clearly demonstrate that jeans cloth was commonly worn by rural Virginians of all classes, and, moreover, the coarse grade of homespun jeans known as Virginia cloth was a preferred material for the daily dress of country gentlemen. Although our event is in June and jeans cloth was more of a cool-weather fabric, the foregoing examples nonetheless provide valuable insight into popular attitudes towards clothing and fashion among rural Virginians in the antebellum period, underscoring their preference for comfortable, practical clothing and disregard for the latest trends.

Linen frock coat, ca. 1840-1855

Homespun linen trousers, ca. 1840-1850

from Lewis Miller’s "Sketchbook of Landscapes in the State of Virginia," ca. 1850

For summer attire in the Virginia countryside circa 1850, cotton and linen predominate for shirting and trouser material as well as for coats and vests, with jeans cloth appearing to a somewhat lesser extent for trousers, vests, and coats. All-wool garments such as a gentleman’s full suit of black broadcloth would generally be reserved for formal occasions. From spring through fall, Lynchburg and Richmond newspapers of the 1840s and 50s abound with advertisements for linen coats, vests, and pants, and straw or palm leaf hats. Summarizing his extensive examination of primary sources, in The Sweetness of Life: Southern Planters at Home Eugene Genovese writes, “in the countryside, gentlemen preferred broad felt or straw hats and white or nankeen waistcoats”.(12)

"Virginia Planter's Family" by Augustus Kollner ca. 1845

Fleshing out our picture of men’s summer attire, we have period images such as Augustus Köllner’s 1840s watercolor “Virginia Planter's Family,” which depicts a gentleman in a white linen suit and broad brimmed straw hat, and Russell Smith’s 1836 oil painting “Baptism in Virignia” featuring gentlemen in black tailcoats or frocks; white, cream, or dove grey trousers, probably of linen or cotton; and a mix of low-crowned, wide-brimmed, light-colored hats, probably of straw, palm, or felt, along with several black felt or beaver hats. While a baptism is a more formal and ceremonious occasion than a barbecue or a camp meeting, the gentlemen in Smith’s painting give us a sense for the finer sort of attire which would be appropriate at Batteaux and Banjos. In another example from “My Uncle Flatback’s Plantation,” Bagby describes the appearance of his title character on a visit to Farmville, Virginia:

See an old gentleman, with a long knotty staff in his hand, a broad-brimmed white wool hat on his head, a heavy iron-gray beard on his chin, a small long-tail black coat, out at elbows, on his back, and tow-linen pantaloons on his nether extremities.(13)

With his “broad-brimmed white wool hat,” black tailcoat, and linen pantaloons, Flatback, whom Bagby presents as the image of a typical Southside planter, closely resembles the subjects of Smith’s baptism painting. Consistent with other characterizations of the plain, rustic, and even careless attire of rural Virginians, we find revealing details in the coarse tow-linen used for his trousers, a material frequently issued to slaves, and his coat with worn out elbows. Flatback is no mere anomaly in this respect, for even Thomas Jefferson was known to go about in patched and threadbare clothing.(14)

"Baptism in Virginia" (selection) by William Thompson Russell Smith, 1836

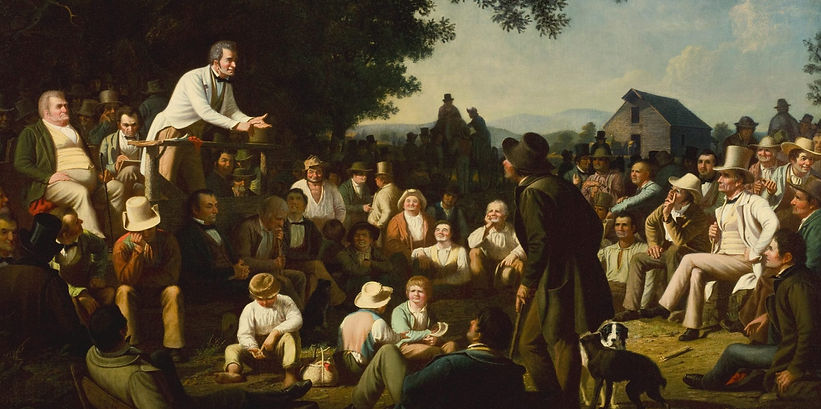

One our richest visual resources is the artwork of Virginia-born artist, George Caleb Bingham. Although Bingham primarily depicts Missouri scenes, with few exceptions his subjects’ manner of dress corresponds with what we find in period accounts of the plain, comfortable, dressed-down, and often homespun clothing worn by rural Virginians in the 1840s through 50s. This should come as no surprise considering the large number of Virginians who settled “Little Dixie,” the section of Missouri in which Bingham lived and painted. Indeed, we have at least one known connection Buckingham in Rev. Henry James Brown, a native of Cumberland County, Virginia, who studied painting under Bingham in Missouri and later returned to teach at the Buckingham Female Collegiate Institute. With most of his figures conservatively dressed in drab or natural colors, with an occasional gentleman in white linen, and some appearing in shirtsleeves, the overall attire and deportment of Bingham’s rural folk and boatmen is characterized by rustic simplicity and a degree of carelessness, the very same terms applied to rural antebellum Virginians by contemporary observers.

"The Jolly Flatboatmen" by George Caleb Bingham, 1846

"Stump Speaking" by George Caleb Bingham, 1853-54

"The County Election" by George Caleb Bingham, 1852

The absence of flamboyant attire in Bingham’s subjects is particularly noteworthy. Although large blocky plaids, paisleys, fat stripes in loud colors, fitted pantaloons, and short frocks with cinched waists feature prominently in popular modern-day notions of 1840s and 50s men’s clothing, such hallmarks of “dandyism,” though common in period fashion plates, are nowhere to be seen in Bingham’s paintings and, judging from all accounts, would have been equally out of place in antebellum Buckingham County as throughout the Virginia countryside.

Southern Planter, Richmond, August 1, 1851

Daily Dispatch, Richmond, July 1, 1853.

Dandies, as antebellum commentators referred to the class of vain and effeminate, typically urban males who vigorously pursued the latest fashions, were a regular object of ridicule and jest in Virginia publications of the period. While a student at the University of Virginia in 1840, a young Robert Lewis Dabney, before he went on to teach at Union Theological Seminary near Farmville and serve as Stonewall Jackson’s chief of staff, derided the vanity of some of his classmates. In a letter to his mother back in rural Louisa County he wrote,

Those students who are able, and are not prevented by principle, dress in a most extravagant manner. I will give you a list of the part of one of their wardrobes, which I am acquainted with. Imprimis, prunella bootees, then straw-colored pantaloons, striped pink and blue silk vest, with a white or straw-colored ground, crimson merino cravat, with yellow spots on it, like the old-fashioned handkerchief, and white kid gloves (not always of the cleanest), coat of the finest cloth, and most dandified cut, and cloth cap, trimmed with rich fur. They do not think a coat wearable for more than two months, and as for pantaloons and vests, the number they consume is beyond calculation. These are the chaps to spend their $1,500 or $2,000, and learn about three cents worth of useful learning and enough rascality to ruin them forever. They have some old standing belles, who bloom with all the perseverance of an evergreen, whom they flirt with as their daily occupation.(15)

In another letter home he declared, “if the students who are here now are to set the measure of morality and honor among the people in the succeeding generation, old Virginia will become but a scurvy place.”(16) Thomas Jefferson so despised foppery, which he associated with a decline in republican virtue, that he favored sumptuary laws, and most respectable rural Virginians of the time would generally have agreed with the likes of Jefferson, Dabney, and William H. Crawford, to name but a few of the most outspoken critics of dandyism from the Old Dominion, in their disdain for fashions they regarded as both symptom and catalyst of the moral and intellectual degradation of the country.(17)

Not surprisingly, rural Virginians tended to lag behind the times with regard to changes in fashion. Jefferson himself, despite being a man of culture and refined tastes, had a reputation for wearing outdated clothes, and period sources show some Virginians wearing fall front trousers and tailcoats through the 1850s and even into the 1860s.(18)

"Tim Longbow," from Virginia Illustrated by David Hunter Strother, 1857. Note fall front trousers.

Meanwhile, the typical summer clothing for slaves in the field consisted of a rudimentary shirt and trousers, typically of plain, un-dyed napped cotton, osnaburg, or coarse, low grade tow-linen. We find documentation of this simple “uniform” in many runaway ads from Lynchburg, Richmond, and other locations in central Virginia, slave narratives from across the South, the writings of George William Bagby and Frederick Law Olmsted, and in Lewis Miller’s Sketchbook of Landscapes in the State of Virginia, a collection of watercolors done in the early 1850s. In "What I Did with My Fifty Millions," Bagby describes the male slaves on a typical Southside plantation "dressed in nappy cotton."(19) And in his comments on Virginia, Olmsted writes,

As to the clothing of the slaves on the plantations, they are said to be usually furnished by their owners or masters, every year, each with a coat and trousers, of a coarse woolen or woolen and cotton stuff… for Winter, trousers of cotton osnaburghs for Summer, sometimes with a jacket also of the same; two pairs of strong shoes, or one pair of strong boots and one of lighter shoes for harvest; three shirts; one blanket, and one felt hat.(20)

from Lewis Miller’s Sketchbook of Landscapes in the State of Virginia, ca. 1850

"Solomon Northup in His Plantation Suit" frontispiece from Twelve Years a Slave, engraving by Nathaniel Orr from illustration by Frederick M. Coffin, 1855.

Runaway ad concerning a Buckingham County slave, Lynchburg Republican, March 2, 1848

Child’s “slave cloth” sleeveless jacket and pants, homespun napped cotton, Louisiana, ca. 1850. From the Collections of Shadows-on-the-Teche.

The following runaway ads, chosen for their representative qualities, affirm Bagby's and Olmsted's descriptions of the clothing typically worn by Virginia slaves, but also contain many interesting details which help flesh out our picture of their everyday appearance.

Had on a low crowned wool hat, tow shirt, tow pantaloons, and coarse shoes, half soled. (Richmond Enquirer, 1849)

He had on when he left a blue mixed homespun frock coat, coarse homespun shirt, black satinet pants, grey mixed homespun vest, homemade shoes, closed with tanned leather strings, a white wool hat, nearly worn out, with a flat crown. (Richmond Enquirer, 1849)

His winter coat was of Nape Cotton, his pantaloons of homespun, and his hat a white one. (Lynchburg Virginian, 1848)

He went off with a white fur hat about half worn, two coats, one of broad cloth and one of jeans, both blue. He also took with him three new cotton shirts, and three pair of pantaloons, two of tow and one of broadcloth, and sundry other clothing not recollected. (Staunton Spectator, 1840)

A brown cloth coat, but little worn, with a pair of striped cloth pantaloons, and a gray cassinet coat, somewhat faded, with a velvet collar; and a pair of new double wove pantaloons, dyed blue, the filling of which is doubled and twisted. He wore a brown cloth cap. (Lynchburg Virginian, 1848)

He had on when he ran off a common gray suit of Jeans Cloth, with a Blue Broad Cloth Coat and other good clothes in his possession. (Augusta Democrat, 1846)

Had on an old homespun coat and pantaloons, so ragged that the original color could not be told. (Richmond Enquirer, 1843)

He had on when he left, a Virginia cloth coat and pantaloons, and an old satin vest. (Richmond Whig, 1846)

Had on a white fur hat, dark brown woolen coat, checked waistcoat, flax and cotton pantaloons; he had finer clothing, among which were a Cassinet coat, blue pantaloons, and a homespun waistcoat, blue and yellow striped. (Richmond Enquirer, 1849)

Had on when he left home a black frock coat, dark homespun pantaloons, and cap. (Richmond Enquirer, 1846)

When last seen he wore a brown jeans dress coat and pantaloons of like material. (Lynchburg Virginian, 1847)

Had on when he left a white fur hat, an old fashioned military coat, made of blue cloth, and brown pantaloons. (Lynchburg Virginian, 1840)

Had on when he left a pair of Burlaps pantaloons, and a white fur hat. (Lynchburg Virginian, 1840)

Had on when he left me a suit of common homespun cloth. (Richmond Enquirer, 1844)

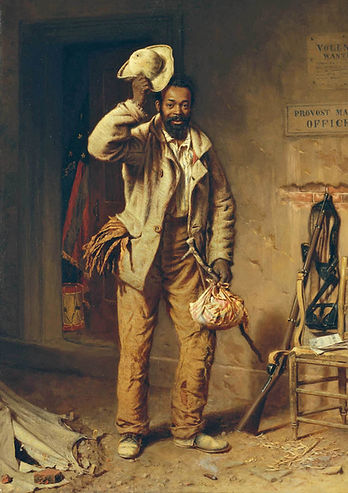

"The Contraband" by Thomas Waterman Wood, 1865. Although this image post-dates our period, the subject's coarse jeans cloth coat, homespun shirt and trousers, and white wool hat are consistent with descriptions of typical slaves' clothing in the 1840s-50s.

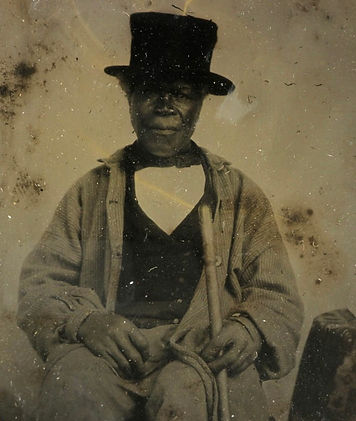

Unidentified man, ca. 1850.

As these examples demonstrate, runaway ads confirm certain basic aspects of slaves' attire — namely the ubiquitous substrate of coarse, homespun garments — but also reveal surprising variety of in slaves' attire, with many subjects' wearing a patchwork ensemble of rough field clothes and garments of higher quality than one might expect. One rather exceptional ad from the January 20, 1842 Lynchburg Virginian describes the attire of a "mulatto" servant who absconded from the plantation of Archibald Moon in the Red House district of Charlotte County,

He can play on the fiddle some... Had on when he left, a white fur hat, a black broad cloth coat, with black cotton velvet collar and cuffs, a speckled cotton swansdown vest, a pair of blue cassinett pantaloons, a bombazine stock, a purple lawn bosom, with single ruffle; took with him a blue Kentucky jeans coat, a pair of black Virginia Cloth pantaloons, one black worsted vest, and one white marsailles.

It is worth reiterating that the fine, even flamboyant, clothing described in this example is an exception to the norm. By far, references to “homespun,” “Virginia cloth,” “jeans,” and "nape" or “napped cotton” predominate in runaway ads. Indeed it rare to find an ad not featuring one or more of these terms, and no other examples in our extensive survey mention anything so extravagant as a “bombazine stock” or “purple lawn bosom, with single ruffle.”

Nevertheless, runaway ads often include references to at least one or two finer quality items, for instance, a broadcloth frock coat or a satin vest, in addition to the coarser garments which likely represent work clothes issued by owners, implying, or sometimes stating explicitly, that the runaway left with more Of slaves in Virginia, Frederick Law Olmsted observed, "On Sundays and holidays they usually look very smart, but when at work, very ragged and slovenly."(21) In another place he wrote,

The greater part of the colored people, on Sunday, seemed to be dressed in the cast-off fine clothes of the white people, received, I suppose, as presents.... Many, who had probably come in from the farms near the town, wore clothing of coarse gray “negro-cloth,” that appeared as if made by contract, without regard to the size of the particular individual to whom it had been allotted, like penitentiary uniforms. A few had a better suit of coarse blue cloth, expressly made for them evidently, for “Sunday clothes.”(22)

Gilbert Hunt, Richmond, Virginia, 1860. Born into slavery in 1780 and trained as a blacksmith, Hunt saved many lives in the infamous Richmond Theatre Fire of 1811 earning him status as a local hero. Hunt purchased his freedom in 1829, attempted to settle in Liberia but returned to Virginia after only eight months. Note the "fashion lag" in Hunt's wardrobe. Although his attire is formal, the actual quality is patched and threadbare.

Unknown slave overseer, ca. 1850, North Carolina.

As Olmsted rightly observes, the finer garments mentioned in runaway ads may be accounted for by the well-documented practice of masters giving slaves hand-me-downs from their own personal wardrobes. Alternatively, slaves, especially those who were skilled craftsmen, artisans, or musicians, could have raised money of their own with which to purchase special clothing items. In our assessment of the information contained in runaway ads, however, we must also consider the fact that some of the clothing runaways took with them were stolen from their masters’ own closets.

Apart from this last possibility, the attire documented in runaway ads bears witness to the fact that slaves, especially house servants, were often better clothed than poor whites. As one New Englander observed in 1832,

The lowest class in Virginia is that of the “poor white man,” or as the negro calls him, the “poor buckra,” He is an object of pity and derision even to the negro himself. These men are gipseys in all but a wandering life, having not only no possessions, but no very distinct notions of property, scarcely making any distinction between meum and tuum — Brought up in ignorance, they live in idleness, and their lives are practical homilies on the importance of common schools, and laws to compel attendance thereon.(23)

Accordingly, we may infer that the coarser clothing recorded in runaway ads parallels the that worn by poor whites who would not have had as much access to the same finer quality items which interspersed many slaves' wardrobes, worn, patched, and stained though those finer clothes might have been. Similarly, despite the fact that cities like Richmond and Petersburg boasted prosperous free black communities where ladies and gentlemen of color went about in high style, freemen were often more poorly clothed than slaves in rural areas.(23) Nonetheless, we also find instances of successful freedmen and their families in antebellum Virginia, some of whom, like Dick Parsons, earned wealth and respect in their communities as batteau captains and even owned slaves themselves.

hi

NOTES

Participants will be portraying locals gathered for an “old Virginia barbecue” on Saturday and a camp meeting on Sunday. Impressions should be representative of Buckingham County, Virginia, circa 1850. Fashions from the 1840s are strongly encouraged, but conservative looks from the 1850s are also acceptable. Impressions may range from upper middle class to poor. Barbecues and camp meetings were focal points of rural community life in antebellum Buckingham County and places like it across the Old South. These iconic events in the rural social calendar brought together all manner and class of folk from the surrounding area, from planter to poor white, slave and free. To recreate the cross-section of society one would have witnessed on these occasions, we welcome a healthy mix of impressions appropriate to our specific setting in rural Southside Virginia. Please consult the historical research available on this site for inspiration and guidance as you build your impression.

Upper class and middling impressions should dress for leisure in an outdoor setting during the summer. Excessively formal or extravagant attire should be avoided. Lower class impressions may dress for work or leisure according to which is more appropriate to an individual's duties for the weekend. Although low in the social order, slaves could be well-dressed depending on their role.

Headwear

1. Broad-brimmed straw or palm-leaf hats recommended

2. Broad-brimmed wool or felt hats, in light colors, i.e.: white, grey, or tan.

3. Other broad-brimmed civilian hats in drab colors or black

4. Caps appropriate for summer in rural Virginia

5. Tarred straw, oilcloth, or “tarpaulin” hats

6. Top hats in limited numbers

Shirt

1. Plain white cotton or linen recommended (“CS issue” shirts acceptable)

2. Striped or checked “homespun”

3. Napped cotton for slaves and poor white s

4. Plain or plaid linseys

5. Printed shirts in limited numbers

*Late 18th/Early 19th century style shirts such as those sold by South Union Mills are acceptable.

*No battleshirts

*Avoid flashy patterns.

Trousers

1. Linen or cotton recommended

2. Jeans cloth

3. Wool if no other option

*Fall front and fly front both welcome.

*Undyed or plain colors prefered

*Stripes and plaids in subdued colors

Coat

1. Frocks and tail coats in cotton, linen, or jeans preferred, wool acceptable.

2. No coat

3. Sack coat

Vest/Waistcoat

1. Linen, cotton, nankeen, or jeans cloth preferred

2. No vest

3. Silk in limited numbers

4. Wool if no other option and you cannot go without a vest.

*Plaid/checked, striped, and plain preferred

*Avoid overly ornate, loud, or flashy patterns.

Shoes

1. Various early-mid 19th century civilian shoes

2. CS brogans acceptable

3. Barefoot (at your own risk)

4. Boots in limited numbers

*For watermen/boatman, well-worn, cut down or low-quarter shoes, preferrably without laces, are recommended.

*Footwear is highly recommended if you are participating as a crew member on an actual batteau. For this activity, simple period correct mocassins or “souliers de boef” such as those sold by South Union Mills are acceptable. Please note, these are not recommended for impressions in our 1845-50 living history encampment.

Cravats, Neckerchiefs, and Neckstocks

1. silk, cotton, or linen in plaid, stripes, plain colors, or prints

2. None

Eyewear

1. Period-correct eyewear or contact lenses

*No modern sunglasses

Accoutrements

1. Cloth or burlap sacks, market wallets

2. Carpet bags

3. Other period appropriate luggage

*No canteens, haversacks, or other military paraphernalia

For your own convenience

PLEASE BRING:

1. Cup (tin, pewter, earthenware, glass, or china)

2. Plate or bowl (tin, pewter, china, earthenware, wood, or gourd shell)

3. Period correct utensils

4. Tent and optional fly (Wall or wedge preferred. Please avoid military-style dog tents.)

5. Groundcloth (oilcloth preferred, gum blanket as last resort)

6. Lantern and candles

7. Bedding (quilts, coverlets, wool blankets, and tick mattresses all welcome)

8. Water in period correct containers (bottles, jugs, jars, or gourds, no canteens)

9. Period correct seating (simple folding camp-seats, lightweight chairs)

10. Period correct food and cooking implements (no "cold handle" skillets)

m

BIBLIOGRAPHY

1. West, Sue Roberson, Buckingham Female Collegiate Institute: First Chartered College for Women in Virginia, 1837-1843, 1848-1863, a Documentary History. Charlotte, North Carolina: S.R. West, 1990.

2. Genovese, Eugene Dominick, and Douglas Ambrose. The Sweetness of Life: Southern Planters at Home. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018. 124

3. Bagby, George William. The Old Virginia Gentleman: and Other Sketches. New York: Scribner, 1910. 73

4. Olmsted, Frederick Law. A Journey in the Seaboard Slave States with Remarks on their Economy. New York: Dix & Edwards, 1856. 91

5. Genovese, Eugene Dominick, and Douglas Ambrose. The Sweetness of Life: Southern Planters at Home. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018. 123

6. Adams, Henry, and John Randolph. American Statesman: John Randolph. Boston: Houghton, Mifflin and Company, 1883, 117-118

7. Ruffin, Edmund.The Diary of Edmund Ruffin. Vol. III: A Dream Shattered, June, 1863—June, 1865. Edited by William Kauffman Scarborough. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1990. 896

8. Johnson, Thomas Cary. The Life and Letters of Robert Lewis Dabney. Richmond, Virginia: The Presbyterian Committee of Publication, 1903. 191-192

9. Early, John. “Diary of Johh Early, Bishop of the Methodist Episcopal Church, South (Continued).” The Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, Vol. 34, no. 2 (1926): 130-37. 133

10. Ibid,. 137

11. Jefferson, Isaac Granger and Rayford W. Logan. Memoirs of a Monticello Slave. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 1951. 21

12. Genovese, Eugene Dominick, and Douglas Ambrose. The Sweetness of Life: Southern Planters at Home. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018. 124

13. Bagby, George William. Selections from the Miscellaneous Writings of Dr. George W. Bagby. Richmond, VA: Whittet & Shepperson, 1884. 69

14. Plumer, William. William Plumer’s Memorandum of Proceedings in the United States Senate, 1803-1807. Edited by Everett Somerville Brown. New York: The Macmillan Company, 1923. 193

15. Johnson, Thomas Cary. The Life and Letters of Robert Lewis Dabney. Richmond, Virginia: The Presbyterian Committee of Publication, 1903. 54

16. Ibid., 55

17. Genovese, Eugene Dominick, and Douglas Ambrose. The Sweetness of Life: Southern Planters at Home. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018. 123-24

18. Randall, Henry S, and Christopher B Wyatt. The Life of Thomas Jefferson. New York: Derby & Jackson, 1858. 507

19. Bagby, George William. Selections from the Miscellaneous Writings of Dr. George W. Bagby. Richmond, VA: Whittet & Shepperson, 1884. 292

20. Olmsted, Frederick Law. A Journey in the Seaboard Slave States with Remarks on their Economy. New York: Dix & Edwards, 1856. 112

20. Ibid., 28

21. Ibid., 123

22. Ibid., 27-28

23. “Virginia: from the New England Magazine,” Phenix Gazette, February 3, 1832, Alexandria, D.C.. 2

z