Foodways in Antebellum Southside Virginia and Guidelines for Meals at Batteaux and Banjos

"The Cook" from from Virginia Illustrated (1857) by David Hunter Strother

Interpreters planning their meals for Batteaux and Banjos should build their menus around foods correct to the season, region, and period we are portraying — summer in Antebellum Southside Virginia. We are fortunate to have an abundance of primary sources on this subject. The following excerpts are just a few highlights selected for their completeness and relevance to our historical setting. Be sure to see the notes and guidelines for your meals further down. The best guidelines, of course, are the words of those who there.

“I am not prepared to dispute these points, but I am tolerably certain that a few other things besides bacon and greens are required to make a true Virginian. He must, of course, begin on pot-liquor, and keep it up until he sheds his milk-teeth. He must have fried chicken, stewed chicken, broiled chicken, and chicken pie; old hare, butter-beans, new potatoes, squirrel, cymlings, snaps, barbacued shoat, roas'n ears, buttermilk, hoe cake, ash-cake, pancake, fritters, pot-pie, tomatoes, sweet potatoes, June apples, waffles, sweet-milk, parsnips, [Jerusalem] artichokes, carrots, cracklin bread, hominy, bonnyclabber, scrambled eggs, gooba-peas, fried apples, pop-corn, persimmon beer, apple-bread, milk and peaches, mutton stew, dewberries, battercakes, mus'melons, hickory nuts, partridges, honey in the honeycomb, snappin'-turtle eggs, damson tarts, cat-fish, cider, hot light bread, and cornfield peas all the time; but he must not intermit his bacon and greens.” -from “Bacon and Greens” by George William Bagby (1828-1883) of Buckingham County, Virginia.

“A stout woman acted as head waitress, employing two handsome little mulatto boys as her aids in communicating with the kitchen, from which relays of hot corn-bread, of an excellence quite new to me, were brought at frequent intervals. There was no other bread, and but one vegetable served — sweet potato, roasted in ashes, and this, I thought, was the best sweet potato, also, that I ever had eaten; but there were four preparations of swine's flesh, besides fried fowls, fried eggs, cold roast turkey, and opossum, cooked, I know not how, but it somewhat resembled baked sucking-pig. The only beverages on the table were milk and whisky.” -from “A Journey in the Seaboard Slave States” (1856) by Frederick Law Olmsted, describing fare at a plantation in Southside Virginia.

from “A Journey in the Seaboard Slave States” (1856) by Frederick Law Olmsted

“We have had some very refreshing rains of late, and the season for planting tobacco and raising vegetables was never better. We are glad of it, for our garden will produce us something to eat, without troubling the market house for what we want. Peas, snaps, potatoes, onions, lettuce, corn, cabbage, tomatoes, salsify, carrots, beets, radishes, parsnips, butter beans, cymlings, cucumbers, grapes, currants, gooseberries, our garden produces; with fresh butter of the good wife's churning: and we shall enjoy them all, and our friend of the Dispatch, too, if he will come and partake of our vegetable diet.” -Richmond Daily Dispatch, June 17, 1854

“Then what appetites we had! The boatman's fare, of middlings and corn-bread, was for a time a prime luxury. When in our idleness we grew capricious, we gave money to the first mate, Caleb, who, in addition to other accomplishments, had an extraordinary talent for catering. Caleb would pocket our cash and steal for us whatever he could lay his hands on: an old gander, a brace of fighting-cocks, a hatful of eggs, or a bag of sweet potatoes. As he frequently brought us twice the value of our money, we did not trouble ourselves with nice inquiries into his mode of transacting business, but ate every thing with undisturbed consciences. Occasionally we varied our fare by shooting a wild duck or hooking a string of fish; but fish, flesh, or fowl, all had a relish that appertains only to the omnivorous age of sixteen.” -from Virginia Illustrated (1857) by David Hunter Strother, describing the fare of boatmen on the James between Lynchburg and Richmond. Corroborating Strother’s account, period newspapers and other sources abound with complaints about boatmen stealing livestock and produce from farms and plantations along the James. As the popular song "De Boatman Dance" attests:

When de boatman blows his horn,

Look out, old man, your hog is gone;

He steal my sheep, he cotch my shoat,

Den put 'em in bag and tote 'em to boat.

“SPLENDID DINNER.—At the Central Depot, 96 miles from Lynchburg, the excurtionists [sic] partook of a splendid dinner, consisting of roast turkey, ducks, geese, lamb, mutton and veal, mountain trout, (boiled,) catfish fried, (of most enormous dimensions, weighing fifty and seventy-five pounds, taken from New River,) catfish chowder, Brunswick stew, oyster soup, pickle, cold slaw, chow chow, fresh oysters, watermelon fresh and sweet, pies, cakes, fruit, indeed every article of food, that could possibly tend to complete a feast.” -from the Richmond Whig, October 7 1856, describing an excursion on the newly completed Virginia and Tennessee Railroad from Lynchburg to Central Depot, near where modern day I-81 crosses the New River at Radford, Virginia.

"Sunday is a day whereon no Virginian will dine alone if he can have his neighbor; and truly there is a good dinner. Ham, (smack your lips, man, 'tis the Virginia ham.) is every day upon the table, supported by cabbage, or a dish of greens. There is no dinner on any day without these. After a dinner, few people here are averse to the hilarity that comes from a glass of good wine, for the grape is honored even in the region of mint juleps and antifogmatics. Nobody, how-ever, dies of apoplexys for men and boys are always mounted — they are half century, and often ride twenty miles to dine. There are few good country inns in Virginia — why? the people are so hospitable, that there are small gleanings for publicans. A stranger finds a welcome at every planter's house,"

-Phenix Gazette, February 3, 1832, account of a New Englander traveling in Virginia.

from "Cornfield Peas" by George William Bagby

“I. By so much as a man is a Virginian, by so much is he a great man. No sane mind will dispute this proposition.

II. Per contra, by so much as a man is not a Virginian, by so much he is not a great man. This proposition will not be disputed by any sane mind.

III. By so much as a man is not a great man, is he a little man, or Yankee, or foreigner. All sound intellects will agree that this is a logical inference.

IV. Wherever you find cornfield peas most abundant, there you find that the Virginia characteristics abound the most. That is a matter of fact.

V. Ergo, it follows that Virginians are the greatest people in the world, because of cornfield peas, and that they differ from each other, are more or less Virginians, and consequently more or less great, in exact proportion to the quantity of cornfield peas they grow and devour; for I take it for granted that no rational eye could see a grown cornfield pea without instantly introducing it to a palate which would immediately become educated and enamored.

The chain of argumentation is complete and profoundly irrefutable.

But examine the physical geography of the great Commonwealth, and you will find that throughout the Tidewater country, and on the south-side of the river Jeems (for mercy's sake do not call it James) cornfield peas are produced in profusion. And where else do you find the unadulterated Virginian, I would like to know! In the Piedmont* region fewer cornfield peas are raised, and consequently the people are not as thoroughgoing Virginians as they should be. They are too fond of making money, and don't care enough about the debates in the Convention. Why, they actually raise pippins in Nelson! When people quit limber-twigs and barkerliners, and get to raising pippins, you may know that cornfield peas are neglected, and New Jersey tastes coming in. I have my opinion of such people." -from “Cornfield Peas” by George William Bagby (1828-1883) of Buckingham County, Virginia. *Bagby distinguishes Southside Virginia from the Piedmont north of the James.

Southern Planter, November 1, 1849

Southern Planter, October 1, 1846

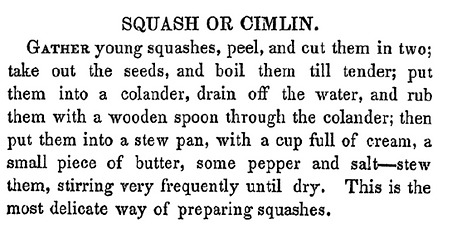

from The Virginia Housewife (1828)

Notes on Foodways in Antebellum Southside Virginia and Guidelines for Meals Batteaux and Banjos

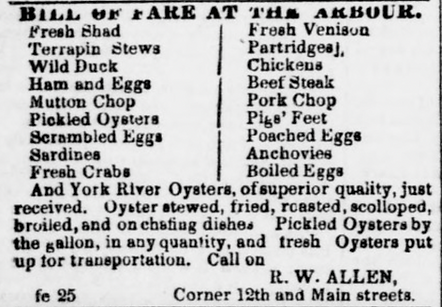

Since rural communities in antebellum Virginia were largely self-sufficient when it came to food production, the bulk of our menu for Batteaux and Banjos should consist of seasonal produce which would have been raised locally. That being said, we are not limited exclusively to what would have been freshly available in Buckingham County in mid to late June. Although the canned foods industry would not take off until the late 1850s and the practice of home-canning lagged even farther behind, a variety of other methods of food preservation were commonly practiced on Virginia farms, specifically drying, salting, pickling, and smoking. Period sources also show that fresh seasonal produce arriving from points south would have been available as the season progressed. Indeed, Virginia itself was a major supplier to Northeastern cities. More exotic produce like lemons and oranges could also be obtained with a fair degree of reliability, especially along a major trade artery like the James River, with lemonade being a ubiquitous feature of antebellum Virginia barbecues.

Spring and summer produce frequently mentioned in receipts, bills of fare, seed inventories, agricultural magazines, and other sources from antebellum Virginia include corn, cabbage, snaps/green beans, butterbeans, okra, tomatoes, cucumbers, squash/cymlins, asparagus, peas, beets, eggplant, field peas (blackeyed and other varieties), Irish potatoes, carrots, onions, peanuts, gooseberries, currants, blueberries, huckleberries, blackberries, cherries, strawberries, figs, June apples, peaches, pears, melons, and watermelons. Again, a number of these are more early spring and some are more late summer crops in central Virginia, but could either have been preserved or brought in from outside.

Virginia Messenger, Volume 5, Number 38, 19 August 1854

Richmond Daily Dispatch, March 10, 1853

Lynchburg Virginian, March 29, 1847

Cool season vegetables like collards and turnip greens — though staples of the local diet — would be mostly if not entirely done by June and do not keep well. Though not in season, sweet potatoes — very popular and grown in large quantities in antebellum Virginia — keep well if stored properly and would still have been available. Some other out-of-season produce like Jerusalem artichokes could be preserved by pickling. Produce like corn and butterbeans which are not harvested until later in the summer would have been available in dried form or brought in from outside. Peaches in June would have been preserved rather than fresh since the early-producing cling varieties had not yet come about. Grapes, not in season until late summer or fall, would have been available as raisins, dried fruit along with nuts such as almonds, pecans, walnuts, and filberts, being a popular dessert of the period. Though Virginians loved and inherently believed in the superiority of their own native grown “watermillions,” with antebellum sources documenting shipments of watermelons up the coast from Savannah, Georgia to New York as early as May some years, people in Buckingham County, Virginia might also have enjoyed this mid to late-summer delicacy on special occasions in June. Smoked meats like bacon and dry-cured country ham were of course staples of the Virginia diet. Pickled oysters also appear frequently in period sources and were widely available in stores. Bread in rural Southside Virginia was usually and sometimes exclusively corn.

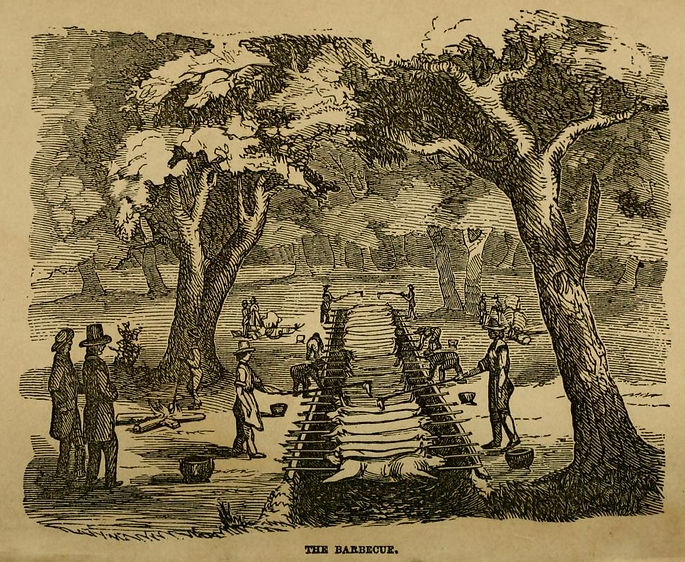

A Virginia barbecue from My Ride to the Barbecue;

or, Revolutionary Reminiscences of the Old Dominion (1860)

Lynchburg Daily Virginian, September 26, 1855

Antebellum newspapers from the Old Dominion are regularly interspersed with announcements for barbecues where, traditionally, dozens of hogs, and sometimes beeves and sheep, would be slow roasted over an open trench for groups as large as several hundred. The barbecue was such an iconic event of the rural calendar in Virginia that it received literary treatment in Charles Lanman's 1850 travelogue, Haw-ho-noo: or, Records of a Tourist and the anonymously penned, My Ride to the Barbecue; or, Revolutionary Reminiscences of the Old Dominion (1860). Fish frys and shad plankings also provided occasions for large gatherings. Lastly, any discussion of historical foodways in Virginia would be incomplete without mention of Brunswick Stew. This Southern classic originating in Brunswick County, Virginia appears frequently in sources from the 1840s and 50s. Traditionally prepared in large cauldrons for big gatherings, it is frequently served with barbecue but can stand on its own just as well.

Alexandria Gazette, June 26, 1855

(from the Petersburg Intelligencer)

Lynchburg Virginian, June, 25 1849

Be aware that modern varieties of certain vegetables are not always exactly like those which were common historically in our region. If you can obtain period correct varieties, so much the better. Also, be sure to consult period receipts and cookbooks, especially those from the region. While certain ingredients may have been available, they were not always prepared the way we would today, or even in ways which we might now consider traditional. For instance, historical sources indicate that the deviled egg, that icon of old time Southern church picnics, does not appear on the scene until the 1870s. However, we do find recipes for “dressed” or “stuffed” eggs in European cookbooks of the period which describe something similar in concept but differing in several important details from deviled eggs as we know them today. Along these lines, a more likely candidate for a picnic dish in our region at the time would be pickled eggs or a recipe found in Mary Randolph’s cookbook which is essentially a Scotch egg without the sausage. Likewise, traditional mayonnaise-based salads such as potato, egg, or chicken salad, etc. do not appear until at least a decade following the War Between the States. Also, bear in mind that many dishes, like salads of lettuce or other fresh greens, though known at the time, are not appropriate for all regions, classes, and social settings. Period sources indicate that the vast majority of rural Southerners, despite having the ability to raise a wide variety of vegetables in their gardens, were generally content to grow and subsist on a relatively limited range of crops — more or less the standard ingredients of “country cookin’” as we know it today — a fact which was frequently lamented by the 19th century editors of The Southern Planter, the popular agricultural journal published in Richmond, Virginia.

RECOMMENDED RESOURCES

Mary Randolph’s The Virginia Housewife (1824), considered the first Southern cookbook, is an indispensable resource and belongs on the bookshelf of everyone with a serious interest in historical Southern foodways. Be aware, however, that many dishes contained in Mrs. Randolph’s book represent the “haut cuisine” of their time and place and do not necessarily reflect common fare of the vast majority of Virginians. https://archive.org/details/virginiahousewif00randrich

Housekeeping in Old Virginia (1878) is highly recommended but requires some discernment and contextual knowledge as it contains some recipes which post-date our period. https://archive.org/details/housekeepinginol01tyre

Virginia Barbecue: A History by Joseph R. Haynes is the best available study on the barbecue tradition in the state where it was born. Also see Haynes' book Brunswick Stew: A Virginia Tradition.

The Williamsburg Art of Cookery by Helen Bullock is another fantastic resource.

Recipes from Old Virginia is also worthy of mention. Though out of print, it can still can be for a very good price if you look for it.